A Frame Without a Screen

On the Cinematics of Architecture

I’m a filmmaker. I’m trained to see like a filmmaker. My mother is an architect. She’s trained to see everything like an architect.

I’ve always felt that cinema and architecture speak the same language. Not just because this is how my mother and I have learned to communicate. But also because in screenwriting classes, scripts are called ‘the blueprint of your film.’ And because both use the language of framing, light, and movement. Both shape how we perceive space and emotion. Both choreograph our attention.

A film compresses time into narrative. A building stretches narrative into space.

Cinema directs how long you look. Architecture leaves the timing to you.

Luis Barragán, my favorite architect, is also the architect who first made me understand that space could hold the emotional weight of a film. His work is often described as cinematic for how it manipulates surface, color, and light to construct emotion. His architecture feels composed through the logic of the camera. Movement through space is guided like a shot sequence. Colors interact with sunlight to create a sense of movement that never leaves the frame of the wall. Barragán understood that color could hold time. He proved that pigment and daylight are not decoration but content, that a wall can register time like an image does. He worked like a cinematographer, controlling light, color, and framing with precision, turning architecture into narrative.

Standing in his studio in Mexico was the first time I asked myself the question: can architecture be cinematic? Could my mother and I have been speaking the same language all along?

Now I know that what unites the two forms is gaze. Both are concerned with how attention is guided and how emotion is framed. A director manipulates the lens; an architect manipulates the body. Each constructs a point of view, defining where looking begins and where it ends. In both, light isn’t decorative, it’s narrative. It decides what exists. The most beautiful buildings, like the most memorable films, understand the psychology of the viewer. Both understand thresholds, concealment, revelation, and contrast. You feel this grammar in Hassan Fathy’s earthen domes, which stage daylight with restraint, and in Ricardo Legorreta’s saturated volumes, where color and mass discipline perception. In a different key, Ricardo Bofill’s La Muralla Roja pushes that logic further: geometry becomes mise-en-scène, a constructed viewpoint where color and light choreograph how the eye moves through space.

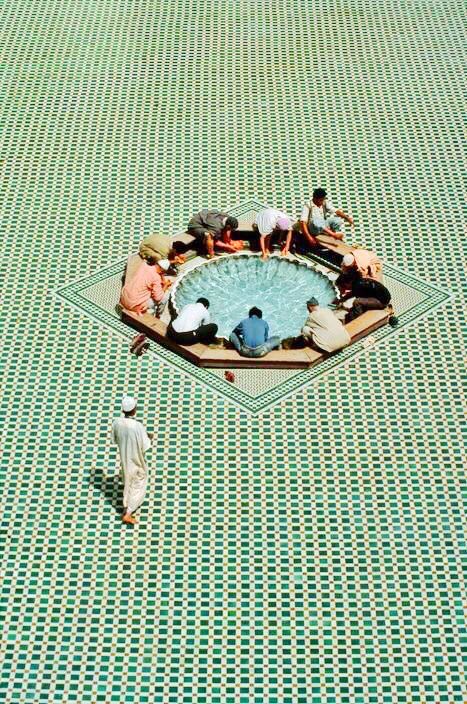

Casa Wabi in Puerto Escondido reduces this to one gesture: an oculus cut from concrete that turns both light and the sky into instruments. The opening is not ornament; it’s an apparatus for perception. The space is cinematic because it is engineered for a precise encounter. Mouassine Mosque in Marrakech works with the same discipline: geometry, shade, and proportion temper the climate and control acoustics so that sound and light arrive with intention.

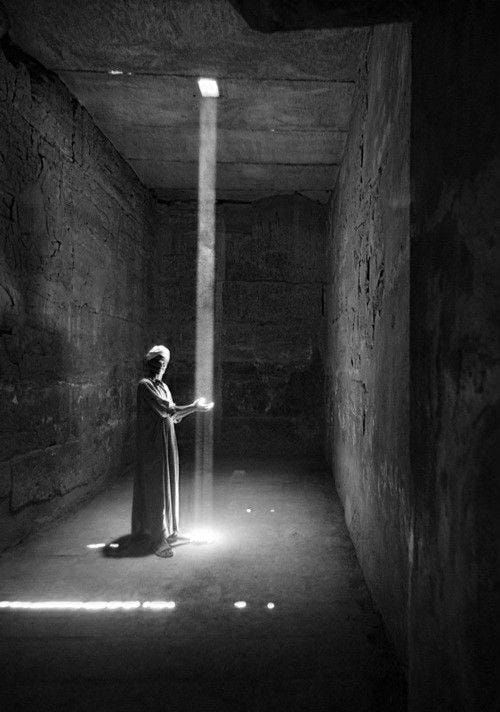

Light, of course, is the original cinematographer. It renders duration visible. It traces motion without recording it. A wall becomes a screen for time itself. Architecture preserves time the same way film does; it frames and reacts to it, responding to the hour, the season, the body passing through. A beam of light across concrete is as temporal as a shot held one second too long. Both are compositions that live and vanish at once.

The idea predates modernism. At Karnak, in the Temple of King Ramses III, shafts and apertures conduct illumination with ritual accuracy. Light there is not ambience; it is a tool that establishes order and emphasis.

Across these places, architecture doesn’t imitate cinema. Rather, it anticipates it, constructing vision through precision.

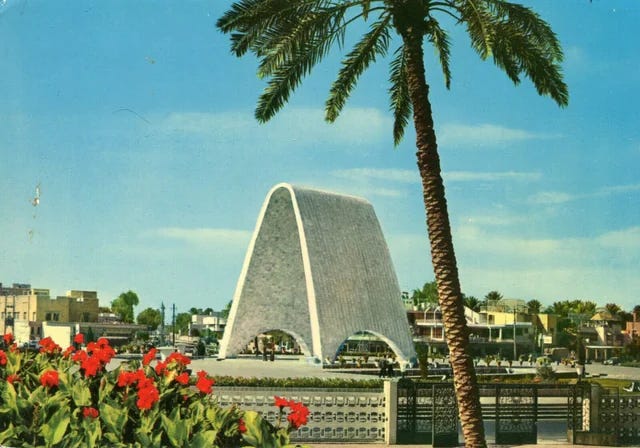

Rifat Chadirji’s buildings in Baghdad carry a similar cinematic sensibility in how they are arrange light, rhythm, proportion, and encounter. His buildings guide perception through repetition: arches that create intervals, façades that reveal space gradually, courtyards that open like held pauses. There’s choreography in how he directs bodies through civic space. Never static. Always unfolding.

Over time, those same structures have taken on a second layer of meaning. War and reconstruction altered them, folding memory into their geometry. What once spoke of a modern future now bears the traces of what was lost. Chadirji once described his buildings as “photographs in stone,” a phrase that captures how architecture and cinema both fix motion into memory. And what is cinema if not that, a composition of memory made visible, alive to the passing of time? His work now feels archival, not because it was built to look backward, but because it holds the residue of what has passed, it honors the past, and it holds the shadows that recall earlier light.

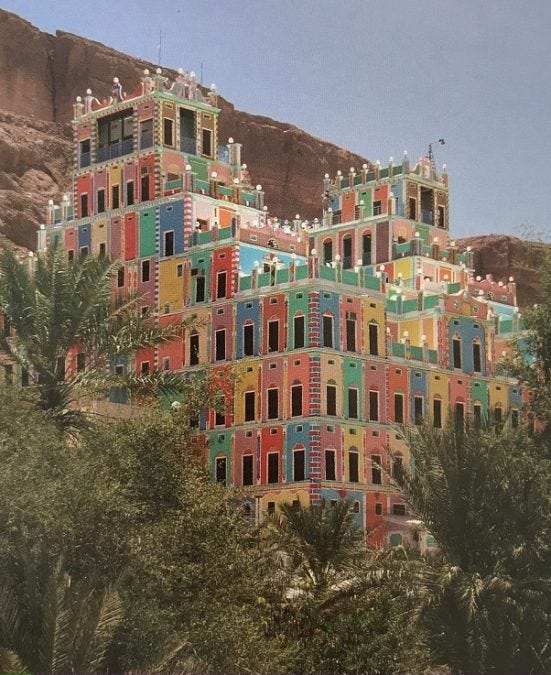

Where Chadirji’s buildings remember through alteration, The Palace of Buqshan in Wadi Dawan remembers through persistence. Both have captures what passes and turn the ordinary act of building into a record of history. But the Palace of Buqshan speaks in another cinematic language. Made from mud brick, it stands tall among the cliffs, its repetition of windows and levels unfold like a musical: structured, lively, and full of rhythm. Each elevation feels choreographed, every color a cue in the larger sequence. Time has added its own choreography too. Weather, repair, and use are woven into the performance.

Both cinema and architecture preserve without freezing and document without declaring pure permanence.

That conversation between architecture, time, history, and memory is the one I live inside in Doha. Doha often feels like a city negotiating its own image. The skyline has changed within a single generation, and the city carries both the new and the persistent at once. The city moves quickly, but not carelessly.

In cinema, cities have always been laboratories for the imagination. The architecture of anime makes this most visible. Films like Metropolis, Tekkonkinkreet, Akira, and Ghost in the Shell transform urban space into emotion. Their skylines exaggerate density, signage, and speed. Not to mirror reality, but to translate how it feels to live inside it. Buildings become expressions of tempo and tension; infrastructure turns into choreography. These imagined cities reveal what real cities try to do: they build atmosphere first, order second. And what film imagines, architecture eventually builds.

Art imitates life, life imitates art.

Doha’s architecture oscillates between the imagined and the lived, between the pristine and the weathered.

Katara Cultural Village feels lifted from an animated film, composed from many cultural influences, arranged into a single, cinematic frame. While, Mina District reads like a Wes Anderson-esque constructed image: pastel facades, careful symmetry, a look so composed it feels almost fictional. A few neighborhoods away, Bin Mahmoud tells another story: pastels faded to matte, no designer name, no perfect light, just homes stacked in concrete, private scenes unfolding without performance. Nothing designed for the camera, yet it’s cinematic because it’s real.

If Mina District is a Wes Anderson film, then Bin Mahmoud is a documentary.

The National Museum of Qatar overturns the conventions of architecture the way an experimental film overturns narrative. There isn’t a single traditional wall; the structure dismantles the grammar of enclosure and replaces it with collision, intersection, and flow. Its design, drawn from the desert rose, turns a natural formation into spatial language, layers of sediment and mineral reimagined as steel and concrete. It’s the country’s geology made visible, matter that holds its own history. Like experimental cinema, it challenges how we read form, undoing the ways we’re used to seeing.

And if cinema constructs vision, architecture constructs space. Home is where they meet.

The home is where architecture becomes most human. Here, architecture scripts intimacy. My own house isn’t cinematic because of its design. It’s cinematic because of how life has settled into it the repetition of mornings, the way rooms remember sound, the quiet scenes that make pattern feel like story. The walls of a home define what we share and what we withhold. A doorway frames the smallest gestures: a glance, a passing shadow and turns them into moments of meaning. Light and sound move differently here, shaped by the thickness of a wall, the distance between rooms, the echo that follows laughter. Architecture makes these patterns visible, turning repetition into memory. The cinematic lives quietly in this arrangement of space and time, in how a home teaches us to see our own lives unfolding.

In the end, both architecture and cinema ask the same thing: to look, long enough and precisely enough, until feeling takes form. My mother and I speak a language split between stone and screen.